December 8, 2025

Earth's Final Frontier: A Century of Exploration

Contributed by Zané van Greuning

The deep ocean is the most unexplored place in the solar system. For nearly a century, exploration advanced in fits and starts, each mission revealing something extraordinary but still leaving 99.999% of the seafloor unseen. But the deep ocean is no longer just a scientific curiosity. It underpins critical decisions across climate, energy, infrastructure, resources, and national security. Orpheus Ocean is building the tools to unlock scalable access to these environments.

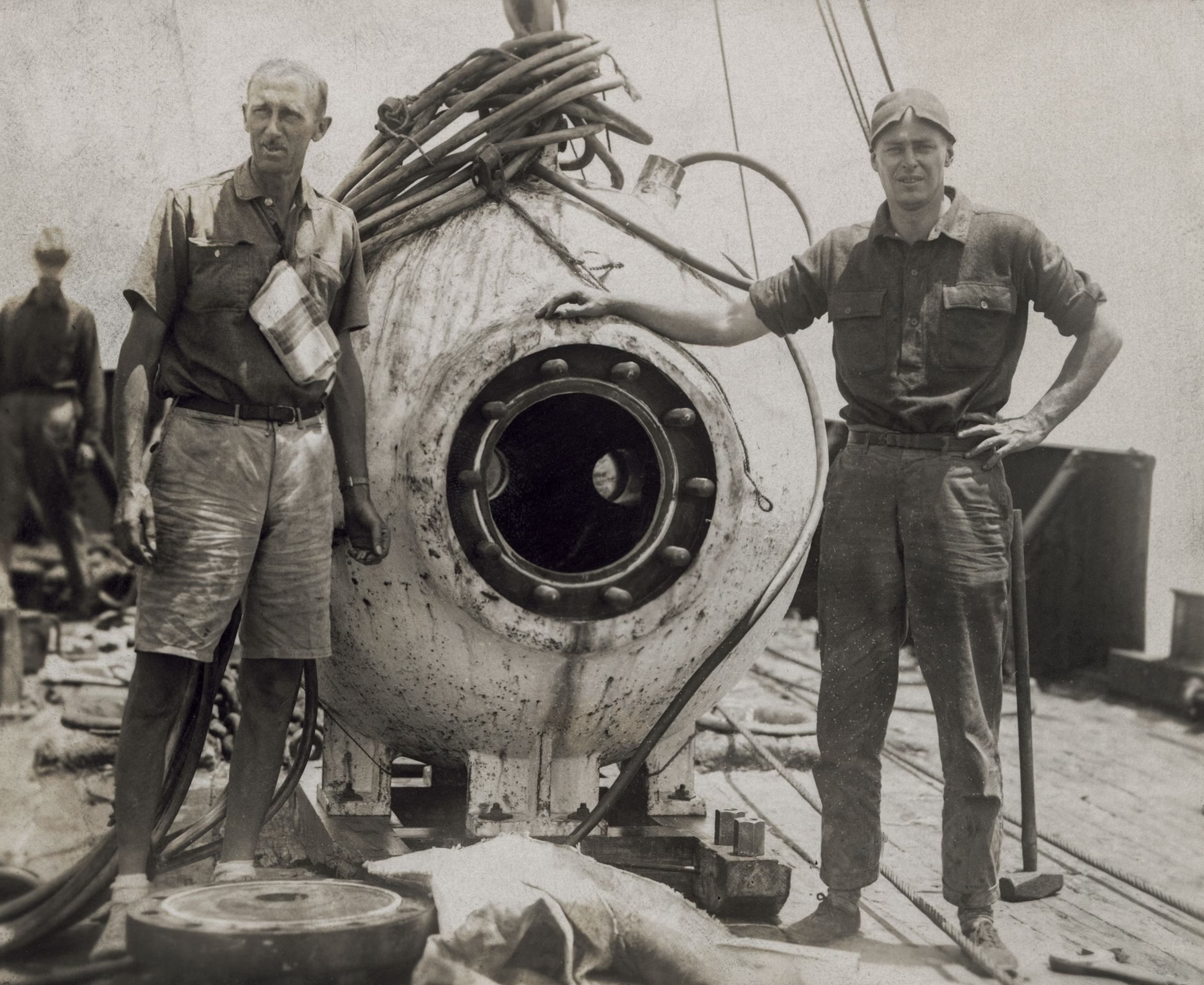

The drive to explore the world beneath the waves is not new. In the centuries before anyone descended, scientists mainly relied on dredging from ships to pull up fragments of a world they couldn’t see. That changed in the 1930s when William Beebe and Otis Barton descended to 900 meters in the unpowered Bathysphere off the coast of Bermuda. They saw a world beyond what anyone had imagined and bioluminescence that seemed to pulse from the darkness itself.

William Beebe (left) and Otis Barton (right) with the Bathysphere. Image source: divingmuseum.org

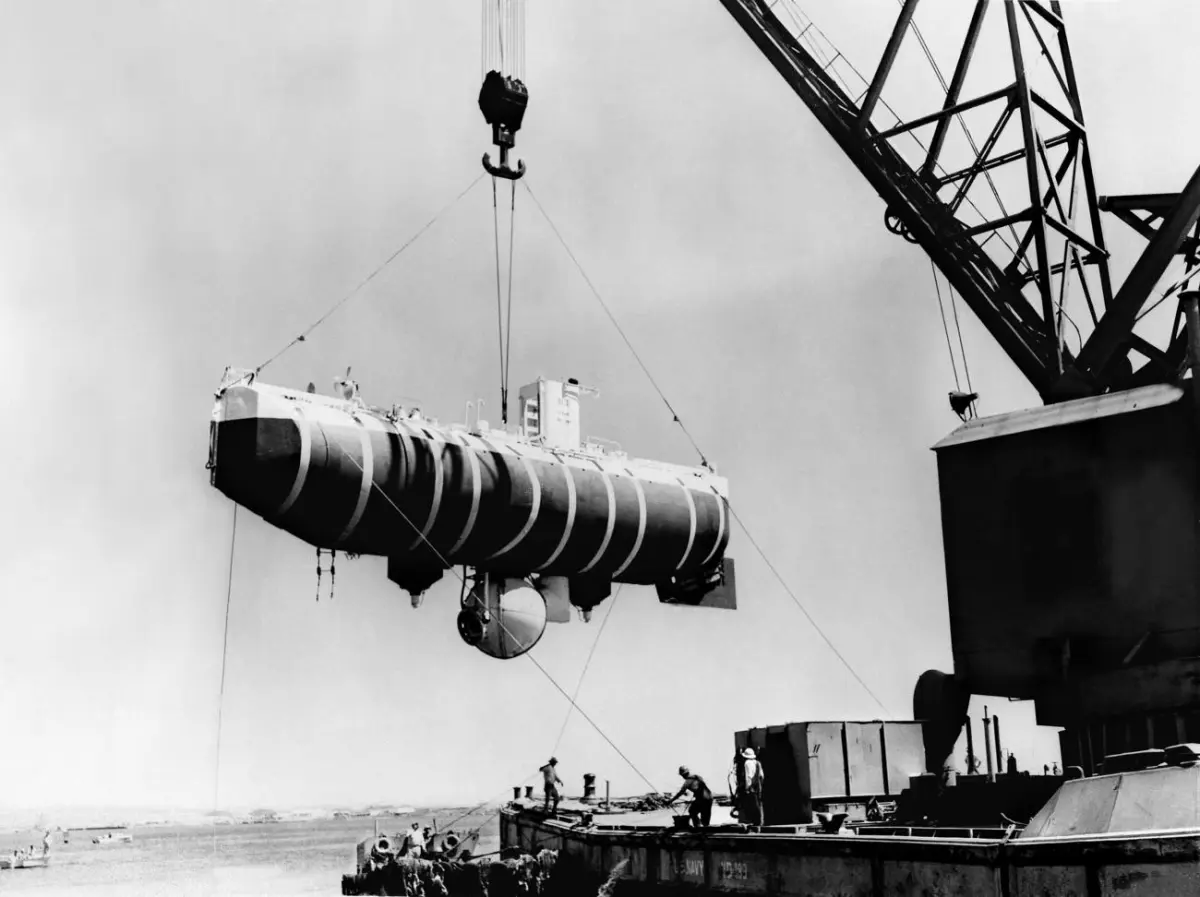

A few decades later, in 1960, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh took humanity even deeper. In Trieste, a pressure sphere mounted beneath a floating gasoline-filled hull, they descended nearly 11,000 meters into the Challenger Deep, the bottom of the Mariana Trench. They spent twenty minutes on the seafloor. No one returned to that depth for more than half a century.

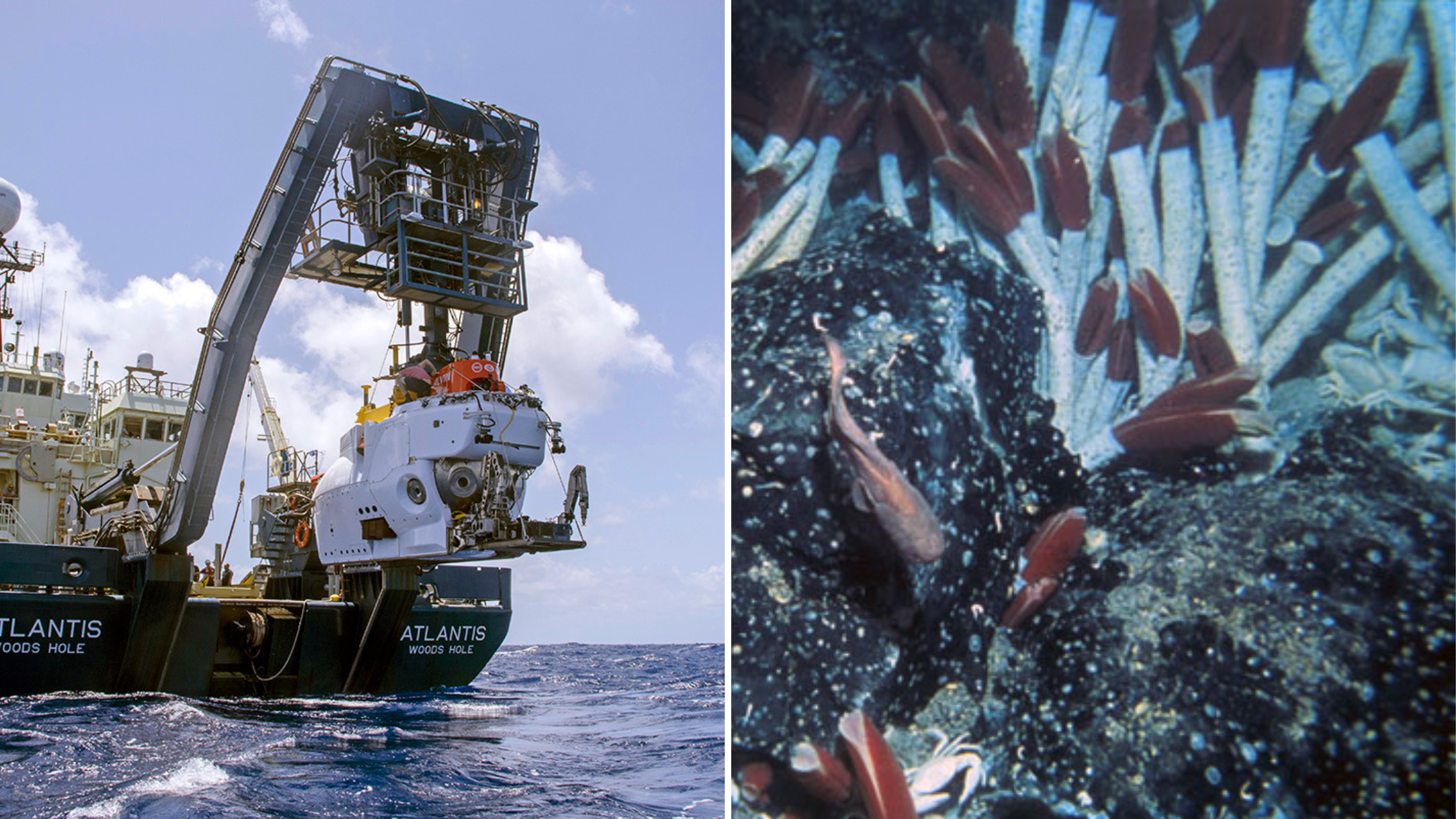

Then, in 1977, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution made a discovery that reshaped our understanding of life on Earth. Working aboard the submersible Alvin, they found hydrothermal vents on the seafloor that supported thriving ecosystems, complete with giant tube worms and otherworldly organisms. These organisms weren’t powered by sunlight like every ecosystem, but by chemical energy rising from beneath the Earth’s crust.

The Trieste used by Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh. Image source: swissinfo.ch

While spectacular, the rarity of these breakthroughs showed how dependent deep sea discovery remained on specialized vessels and infrequent missions. Each required a custom vessel, a large ship on the surface, and teams of people dedicated to a single point of exploration. Discoveries were few and far between and the deep ocean remained largely untouched.

As technology progressed, humans shifted from going down themselves to sending robots in their place. Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) offered high-quality imaging, precise positioning, and manipulation through robotic arms. However, they have the intrinsic limitation of being connected to a surface ship by a heavy tether, which restricts mobility, slows operations, and confines work to the immediate reach of the vessel.

The Alvin submersible developed and maintained by WHOI (left) and image captured of seafloor tube worms (right). Images: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) removed the tether and opened a new chapter of unmanned exploration. AUVs could travel independently underwater, far from surface support, and return with data. They enabled missions that were previously impossible, from locating aircraft wreckage like Air France Flight 447 in the deep Atlantic to producing the first detailed maps of under-ice terrain in Antarctica. Yet many AUVs were still extremely financially and operationally intensive, relying on large ships, complex logistics, and substantial support crews. Exploration continued to happen in discrete, one-off expeditions.

Even today, with modern tools, major discoveries emerge. Earlier this year, scientists discovered a new chemosynthetic cold seep ecosystem at over 9,000 m, potentially indicating that the deep seafloor is storing more carbon than previously thought. Discoveries like this change our understanding of the planet, and also highlight the problem. If important discoveries are still happening when we explore the deep ocean, what are we missing in the places we haven’t reached? And what does that mean for industries like energy, minerals, infrastructure, and biotechnology that depend on accurate information from these environments?

The need for deep ocean exploration has now become a necessity. Demand for critical minerals is accelerating as countries build clean energy infrastructure, yet decisions about where and how to source sustainably require huge amounts of independent baseline data. Marine biologists searching for new compounds and biomaterials need consistent access to ecosystems that may hold the next breakthroughs in medicine. Nations that depend on subsea cables for communication, finance, and security require near real-time awareness of what is happening on the seafloor as global tensions and infrastructure risks rise. Across all of these domains, the pace of activity will continue to increase, and it requires the quality and scale of information to match. We cannot protect what we cannot see, and we cannot manage what we cannot measure.

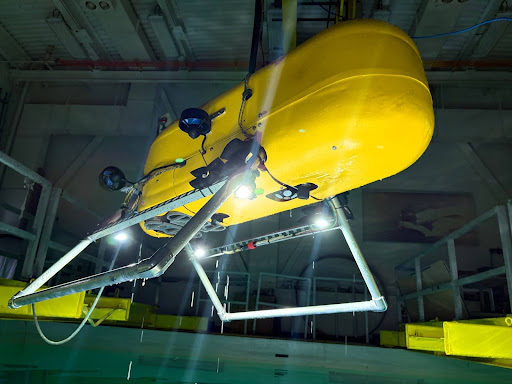

The Orpheus AUV during tank testing in New Bedford.

At Orpheus Ocean, we’re presenting a new model for how to access the deep ocean, suited for this next wave of ocean industries. Traditional systems are powerful but expensive to mobilize, slow to redeploy, and structured around infrequent, ship-dependent missions. Orpheus is built on different principles. Our vehicles are agile, requiring minimal onboard infrastructure and allowing rapid deployment almost anywhere - even from uncrewed surface vessels. They’re adaptable, able to switch payloads or respond to what they encounter on the fly, rather than waiting for another expedition. And they’re affordable enough to scale into coordinated fleets instead of relying on a single, exquisite asset. Together, these pillars shift deep-sea exploration from episodic campaigns to continuous, scalable capability.

Improved access to the deep ocean could give us the clarity needed for industries to develop sustainably. For more than a century, our understanding advanced through singular expeditions that offered extraordinary glimpses but left most of the seafloor unmeasured. Those early missions showed what was possible with the tools of their time. Now we’re building the technology to move beyond these limitations and truly reveal Earth’s final frontier.

If you’re working in ocean science, resource management, infrastructure, or environmental monitoring, or if you simply believe in the value of exploration for its own sake, get in touch to see how we can help you illuminate the deep.

Join our newsletter for updates